Let us take a break now from our look at the successive sub-races of the Atlantian Root Race. We turn our attention now to the civilisation that was developed during this root race, especially the Toltec, the 3rd sub-race, which represented the zenith of the whole root race.

It would not be a wild assumption that the history of the Atlantean Race, as of the Aryan Race, was interspersed with periods of progress and decay. Eras of culture were followed by times of lawlessness, during which all scientific and artistic development was lost, these periods again being succeeded by civilisations reaching still higher levels. Think of our history of the Bronze Age Collapse, in 1,2000 B.C.E., or the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the return to petty kingdoms.

The following description, therefore, applies to the periods of culture; and, whilst not exclusively applicable to any one sub-race, it may be taken to apply principally, as already mentioned, to the great Toltec civilisation, the chief of all the Atlantean civilisations.

The government was autocratic and, under the Divine Kings, no system could have been better suited for the populous. Democracy, in many instances, is overrated. It was planned by the wise for the benefit of all and not by special classes for their own advantage. Hence the general comfort was immensely higher than in modern civilisations. Governors were held accountable for the welfare and happiness of their provinces and crime or famine was regarded as due to their negligence or incapacity. Rulers were drawn chiefly from the upper classes, but aptitude rather than class was the necessary qualification. Sex was no disqualification for any office in the State.

Music was practised, but it was crude and the instruments were primitive, although a yak herder on the Tibetan plateau may resonate with the sounds they produced. All the Atlanteans were fond of colour, both the insides and the outsides of their houses being brilliantly decorated. The art of painting, however, was never well established, though there was some kind of drawing and painting. Sculpture was widely practised and reached a high degree of aesthetic beauty. It is interesting that if you look at our recognised ancient cultures, it was sculpture, again, which predominates in our estimation of their achievements.

It became customary for every person who could afford it, to place in one of the temples an image of themself. These were carved in wood or hard black stone like basalt, or even in aurichalcum, a metal mentioned by Plato to have been found in Atlantis. There was, of course, gold or silver as well. The result was a fair resemblance of the individual, sometimes a striking likeness.

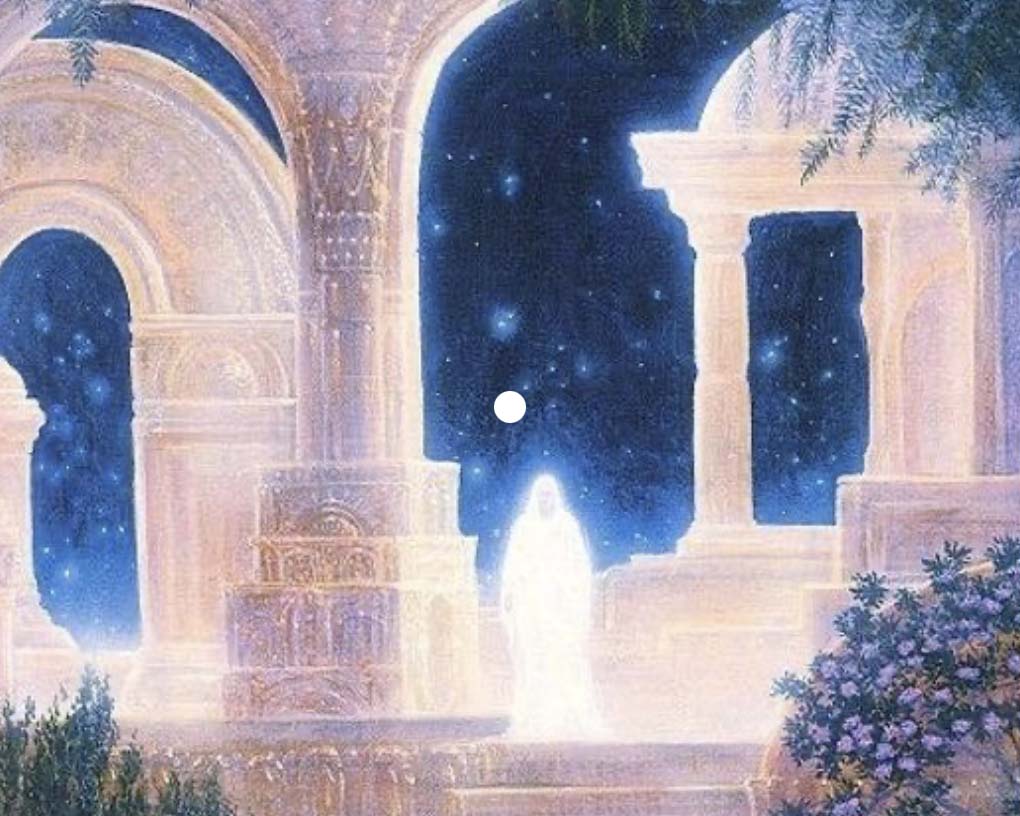

Architecture was the art most widely practised, the buildings being massive and of gigantic proportions. Houses were built detached, even in cities, encompassing up to four blocks sometimes surrounding a central courtyard in the middle of which was a fountain. A characteristic feature of the Toltec houses was the tower that rose from one of the corners or the centre of one of the blocks. An outside spiral staircase led to the upper stories and a pointed dome terminated the tower, this often being used as an observatory.

Some houses were ornamented with carvings, frescoes or painted patterns. The windows were provided with a material similar to glass, but less transparent; maybe it was alabaster. The interiors were furnished, but not in elaborate detail; nevertheless, the life was highly civilised of its kind.

The temples were huge halls, even more stupendous than those of Egypt. The pillars supporting the roofs were square, or occasionally round. In the days of the decadence of the Toltecs, the aisles were surrounded by innumerable chapels containing statues of the more important inhabitants, ceremonial worship of the images being carried out by priests engaged for the purpose. The temples also had their towers and domes, which were used for sun worship and as observatories. The interiors of the temples were inlaid, or even plated, with gold and other precious metals, these metals being obtained by transmutation, this being a private industrial enterprise by which the alchemists earned their living. Gold, being more admired than silver, was produced in much greater quantity.

Gold, silver and aurichalcum were the metals most used for decoration and domestic utensils. Armour was inlaid with these metals, being used merely for show in pageants and ceremonies; golden helmets, breastplates and greaves over the shins, were worn on such occasions over tunics and stockings of brilliant colours – scarlet, orange and a very exquisite purple.

Buying and selling took place privately, except when large public fairs were held in the open spaces in the cities. It would seem that we have not advanced our style of living until very recent times.

Up to about 800,000 years ago, Toltec was the universal language, though remains of the Rmoahal and Tlavatli speech survived in remote districts. All the languages were agglutinative, Chinese today being the nearest analogue. All through the ages the Toltec language remained fairly pure and survived, with slight alterations, for thousands of years. It was still present in Mexico and Peru, though modified, in pre-Colombian times.

All schools were endowed by the State and primary education was compulsory, but reading and writing were not considered necessary for workers in the fields or handicrafts. Children with aptitude were drafted into the higher schools at the age of twelve, where they were taught, as was most appropriate to each child, agriculture, mechanics, hunting and fishing, etc. The properties of plants and their healing qualities formed an important branch of study; there were no recognised physicians, but each person knew something about medicine as well as magnetic healing.

Chemistry, mathematics and astronomy also were taught, the object being the development of the student’s psychic faculties and instruction in the more hidden forces of nature. In this category were included the occult properties of plants, metals and precious stones, as well as alchemical transmutation. As time went on, they were principally occupied in developing the personal power, which Bulwer Lytton called vril, and the operation of which he fairly accurately described in The Coming Race. As decadence set in, the dominant classes monopolised for themselves the educational facilities and natural aptitude was disregarded.

Having no sense of the abstract, the Atlanteans were unable to generalise; for example, they had no multiplication table; arithmetics was to them a system of magic, a child having to learn elaborate rules without ever knowing the reason for them. Thus four sets of rules for mathematical magic had to be memorised for every combination of numbers from 1 to 10, with regard to addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. Most of their calculations, however, were made by an abacus or framework, something like that now used by the Chinese and Japanese. The Atlanteans were clever at amassing facts and had prodigious memories.

The habitual use of clairvoyance enabled them to observe the processes of nature, now invisible to most, so that science was carried far, its applications to arts and crafts being also numerous and useful. They had knowledge of forces, which today has been lost. One of these forces was employed to propel both air- and water-ships; another for changing the attractive force of gravity into a repelling force, so that the raising of gigantic stones to a lofty height was a regular occurrence. The subtler of these forces was not applied to machinery but was controlled by willpower, using the thoroughly understood and developed mechanism of the human mind and body.

Agriculture received a good deal of attention, experiments being carried out in the crossing both of animals and plants. Wheat, for example, was crossed with the indigenous grasses and produced oats and other of our cereals. Less satisfactory were the attempts, which produced wasps from bees, and white ants (termites) from ants. From an elongated melon with scarcely any pulp and full of seeds, they produced the plantain or banana. As a card-carrying agronomist, what has just been recounted would cause consternation. Today, we can trace the origins of the varieties of food we eat today. We have set ourselves a narrative that it all started less than 12,000 years ago. Why? Because in the records we have, we see settlements that seem to be pre-agriculture and when we date them, usually through the pottery they used, we conclude that the agricultural revolution got underway about 9,000 years ago. What, however, if this was not the result of people discovering agriculture, but them rediscovering it? Something to ponder. Consider the horse. It evolved in North America, yet it was reintroduced to the indigenous population by the conquistadors.

Among domesticated animals, they had creatures like very small tapirs, which fed on roots or herbage, or on whatever came their way, like the modern pig. They also had large cat-like animals and wolf-like ancestors of the dog.

Their carts were drawn by creatures somewhat like camels, Peruvian llamas being probably descended from these. The ancestors of the Irish elk roamed about the hills, semi-wild wild but still under the control of the humans.

Artificial heat and coloured lights were used in crossing and interbreeding different kinds of animals, to speed up the process. They worked especially with amphibian and reptilian forms, which had run their evolutionary course and were ready to assume the more advanced type of bird or mammal. Acting in cooperation with the Manu, from Whom all improvements in type, domestic animals like the horse were produced. But when war and discord set in, towards the end of the Golden Age, humanity began to prey on each other; and the animals, left to themselves, followed our example and also began to prey on one another. Some were trained by humans to hunt and thus from the semi-domestic cat descended the leopard and jaguar. It seems that the lion would have been more gentle and a powerful servant for purposes of traction; had humanity fulfilled the task entrusted to them by the Manu. In fact; if humanity had done all their duty, it is quite conceivable that we might have had no carnivorous mammals. Remember, we are talking about a domestication process that lasted for millions of years. Something that modern science could not conceive of.

On that sobering thought, let’s leave it there for today and look at the City of the Golden Gate in more detail next time.