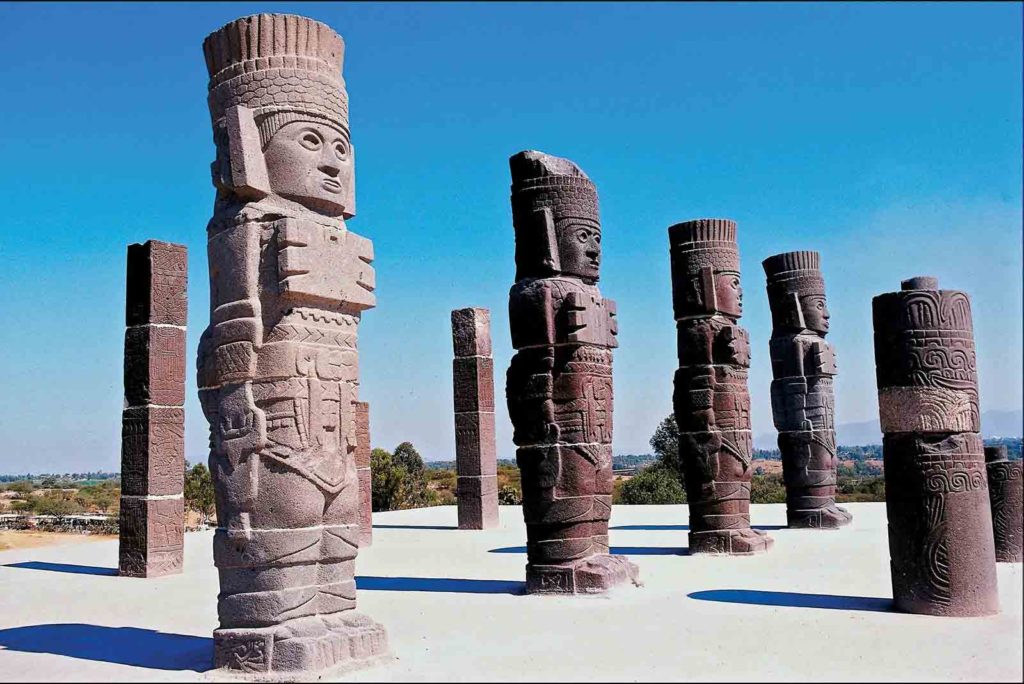

In our look at the social structure of the first three sub-races of the Atlantian root race, references have been made mainly to the Toltec civilisation, the 3rd sub-race. The naming of this sub-race hints at where its cultural influences may still be felt in our current history of ancient cultures. It is important to understand that the Toltecs did not call themselves this. It is we, who have linked their culture to what is a vestigial remnant that we have dated to have existed in the last few millennia. Again this is a misrepresentation of where this link connects to, although echoes of it persist to this day. So, let us delve into a society that existed outside our current timeframe for civilisation, yet it is reported by those that were able to interrogate the Akashic Records, to have existed. Let us review the information gleaned and reflect on how this society was structured and what we can still learn from it.

The civilisation of Peru, about 12,000 B.C.E., closely resembled that of the Atlantian Toltec Empire at its zenith and was, in fact, an attempt to revive, though, of course, on a much smaller scale, the original Toltec civilisation. We may therefore describe certain features of the Peruvian system as an example of Atlantean civilisation. This account is an abridgement from Man Whence How and Whither, by Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater.

Let us start with the government, which was autocratic, for the Ruler – either the Manu Himself or His Lieutenant, some Adept from a far higher evolution – was the only person who really knew anything, so that he had to take control of everything. The keynote of the system was responsibility. This went right to the top. If an avoidable situation, such as the inability of a person to find suitable work, or the illness of a child and the absence of proper attention occurred, it was regarded as a slur upon the administration, a blot upon the reign, a stain upon the personal honour of the king.

This antediluvian Empire was divided into provinces, these being subdivided into cities or smaller districts. From here, the population was divided into groups of 100 families and then again into groups of 10 families. Officials, deemed to be responsible, were in charge of each unit, the honour for an official was being involved in the perfect contentment and well-being of everyone within his or her jurisdiction. Vigilance and attention to duty were ensured not by outer law but by the universal feeling among the governing class, a feeling akin to the honour of a gentleman, (a very Victorian way of looking at things). Anyone who neglected their duty would be considered an uncivilised being and regarded with horror and pity much in the way mediaeval Europe regarded an excommunicated person.

Living under such conditions, laws were almost unnecessary and there were no prisons. Every citizen looked upon their life in the Empire as the only life worth living. If a person fell short of their duty, the officer in charge would reprimand them. If this individual failed to change their behaviour, it led to the only punishment – exile.

The officials were known as ”Fathers”; there was practically no law for them to administer, but they arbitrated in case of disputes. Officials were easily accessible and made periodical tours through their domains so that they could see for themselves that all was well, and so that anyone could consult them or appeal to them if he so desired. I see in this governing style something reminiscent of the patrol officers stationed in Papua New Guinea during the Australian administration of the then colony. The British had a very similar feeling about their divine destiny to lead the colonial inhabitants of India. You can imagine their shock after the first Indian mutiny when the officers found their subordinates no longer quiescent to their wishes.

Births, marriages and deaths were registered with scrupulous accuracy and statistics were compiled from them. Each Centurion recorded on a small tablet – the precursor of the modern ”card” system – the name of every person in their charge, and the principal events in their life.

The land was not only carefully surveyed and parcelled out, but its composition was analysed in order to put it to the best use. Every town or village was allotted an amount of land proportionate to the number of its inhabitants. Half the produce was for the cultivators and their families, in proportion to the number of mouths to be fed; half for the community. The government was always ready to buy surplus grain, which it stored in huge granaries, in case of famine or other emergencies.

Of the half share of land belonging to the community as a whole, one-half, i.e., one-quarter of the whole, was considered the land of the Sun and had to be cultivated first. Then a person was free to cultivate their own land. The last allotment was the quarter share belonging to the King. The same order of precedence applied to the use of irrigation infrastructure. A similar division of produce was made in the case of manufactured goods and mineral products.

As has been mentioned in previous presentations that from his share, the King, maintained the entire government, paying their salaries and expenses. He also built and maintained all public works, such as roads, bridges, aqueducts and granaries, which stored sufficient food to feed the whole population for two years. The King also maintained the army.

With the produce of the land of the Sun, the priests maintained the splendid temples of the Sun all over the land, with a magnificence which has never been approached elsewhere on earth. Remember, this all got washed away after the final destruction of Poseidonis in 9,564 B.C.E. The priests provided free education to the entire youth of the Empire, including technical training up to the age of twenty, or even later. They also took complete charge of and maintained, every sick person, who thus became a ”guest of the Sun.” If the sick person were the breadwinner, their dependents also became ”guests of the Sun,” until the person recovered. Lastly, the priests provided full maintenance in retirement, for all over the age of forty-five except the official class. Now that is what I call a pension system. Forty-five may seem a young age to retire but ask yourself, at this time how long do you think an average life span was?

Officials and priests did not retire at the age of forty-five, except in case of illness. It was considered that their wisdom and experience were too valuable not to be utilised; so in most cases they died in harness. From its stated responsibilities, you can see why the land of the Sun was given precedence in cultivation and irrigation. It was from the produce of this first quarter of the land that supported the religion, education and the care of the sick and aged. The whole system worked so admirably that poverty was unknown, destitution was impossible, and crime was practically nonexistent. Exile was the worst punishment as mentioned. Barbaric tribes from outside the confines of this well-ordered system of governance became absorbed into the system as soon as they could be brought to understand it. It should be noted that the term “barbaric” was coined by the Greeks to define any tribe that did not speak Greek!

These “Toltecs remnants”, as we have decided to call them, worshipped the Sun, but regarded the physical sun as a symbol of that from which everything came. They did not seem to have any clear idea of reincarnation but were certain that a person was immortal. They held that the person returned to the Spirit of the Sun. Their religion was essentially joyous, grief or sorrow being held to be wicked and ungrateful. Death was regarded as an occasion for solemn and reverent joy. Suicide was looked upon with the utmost horror, as an act of grossest sinfulness and was almost unknown.

In their public services praise, but never prayer, was offered daily to the Spirit of the Sun. Why the difference? When you praise, you are acknowledging something or someone. When you pray, you are usually “begging” for something. Subtle but important difference. Fruit and flowers were offered as tokens of what they owed to the Spirit of the Sun. Sermons were simple, with pictures and parables being largely used. The people were taught that what the Sun did for their bodies, the Sun did also for their souls, both actions being continuous. Humanity should aim at being perfectly healthy, physically and morally, thus becoming themselves minor suns, radiating out strength, life and happiness. They had accurate knowledge of the radiation of superfluous etheric vitality from a person in good health.

What can we draw from what we have learned today? We have a society that seemed, according to Besant and Leadbeater, that live in harmony with themselves and their environment. They were a simple, agrarian society that was organised around production and the sharing of surpluses in such a way that the whole of the society was able to enjoy the fruits of their collective labour. The society was very hierarchical, but this hierarchy was not sustained by greed or a need to control others. It too, worked for the simple but universal goal of service to all. Watching over all of this was the “Sun”, the supplier of vitality, not just for their bodies but their souls as well.

In the next presentation, we will delve deeper into other aspects of this society.